In Spring 1981 I was finishing up my medical internship at a busy teaching hospital. Despite a crazy on-call schedule and chronic sleep deprivation, I had also managed to successfully complete a diploma course in computer science at a local college. I heard from a colleague that one of the hospital’s consultant physicians has been gifted an Apple II computer and was interested in using it to manage medical data. At the time, the idea of using a ‘personal computer’ in medicine was both novel and exciting.

In July 1981 we embarked on a six month project to design and implement an Apple II database system to manage information related to gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy procedures performed at Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin, Ireland.

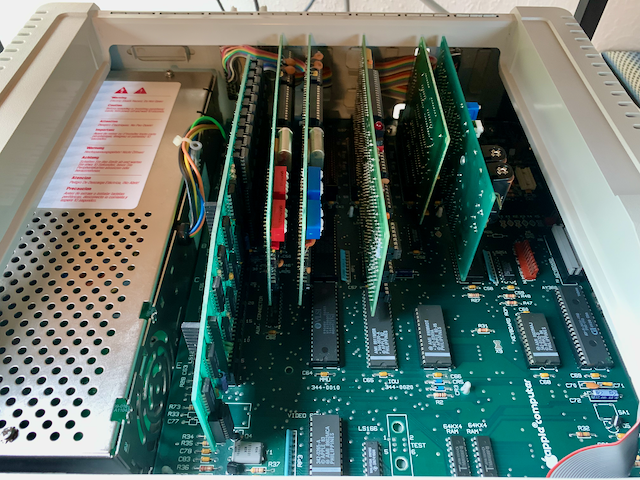

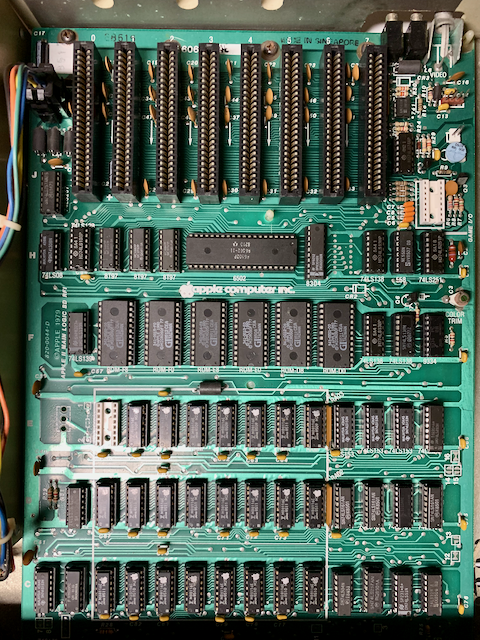

The hardware consisted of an Apple II Europlus with 48K of RAM, two 140K floppy disk drives, a 40 column monochrome display monitor and an Anadex DP-9501 dot matrix printer. The database system was named the Computerized Endoscopy Data Management System (CEDMS).

Initially we considered implementing CEDMS using an Apple II commercial database software package called the CCA Data Management System (Personal Software, 1980). However, following a detailed evaluation, it was clear that CCA was not suited to our needs and we instead chose to develop a custom database application written entirely in AppleSoft BASIC.

The CEDMS project had three major goals: (1) the database should support storage, retrieval and reporting of the core administrative and clinical data related to GI endoscopies performed at the hospital; (2) the system should be turnkey, easy to use and tolerant of user errors and (3) given that approximately 5000 GI endoscopy procedures were performed at the hospital each year at that time, we would need a storage model that could accommodate that volume of data using only 140K floppy disks. In 1981 a Corvus 10MB hard disk for the Apple II cost $5000 (approximately $17,000 today) and was beyond the project’s budget.

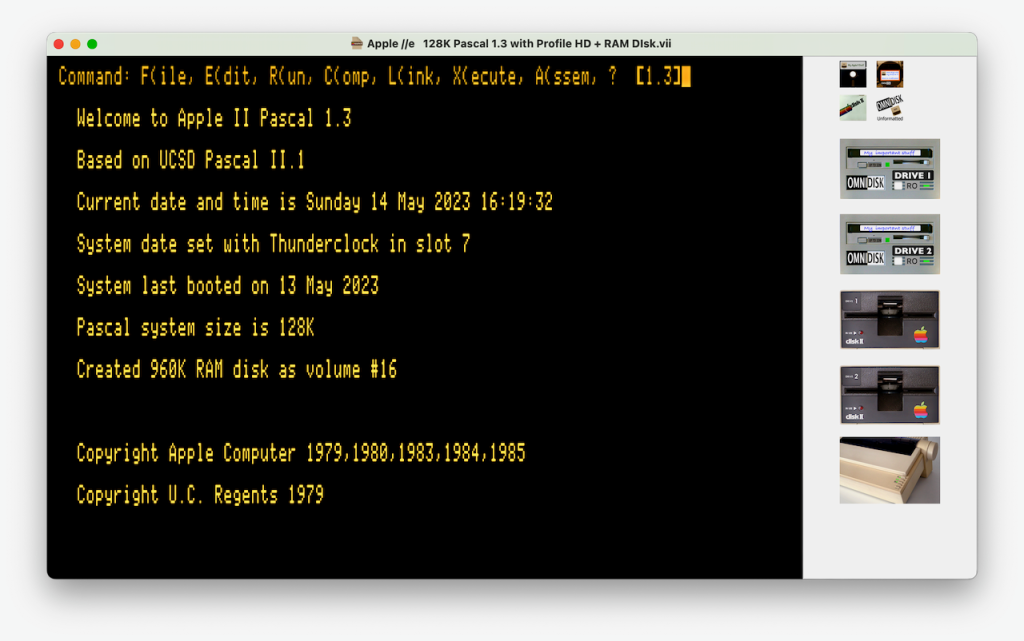

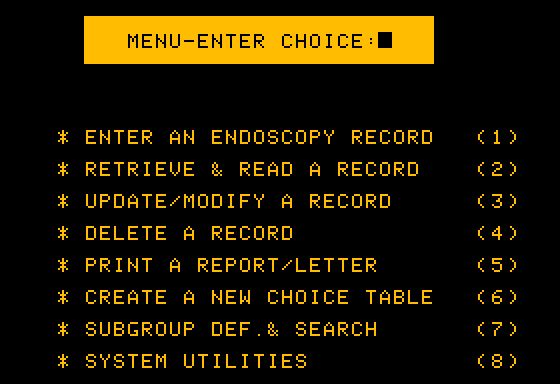

CEDMS Main Menu

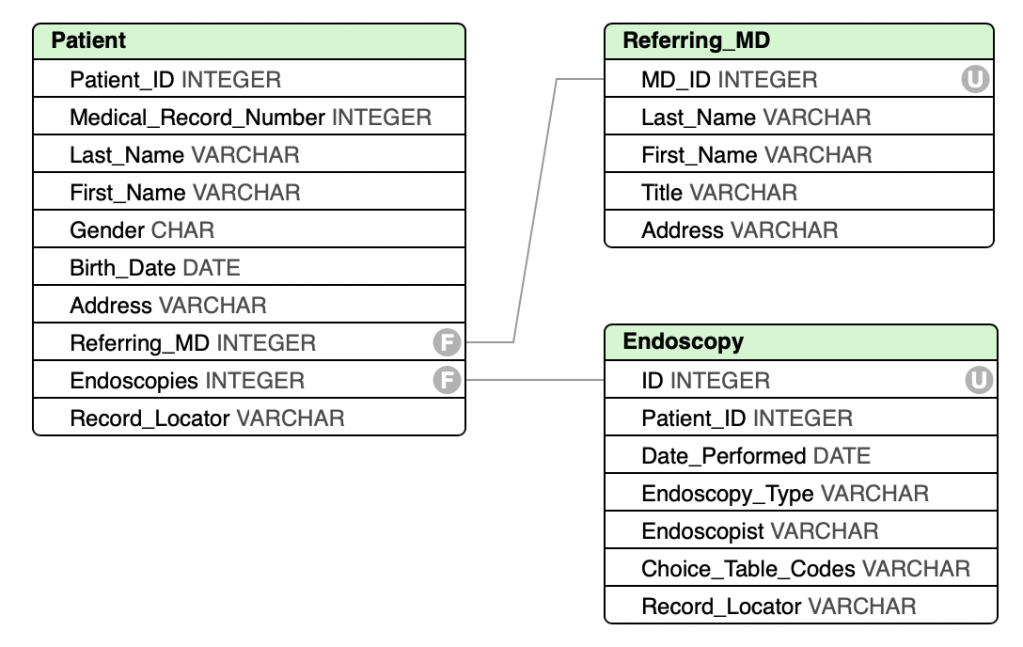

The CEDMS database was implemented using the Random-Access Files feature of Apple II DOS. Each data file contained a set of sequentially numbered fixed-length records that could be directly accessed from BASIC using the record’s sequence number. To support searching, data file records were indexed using a b-tree of calculated keys. This design created a simple Indexed Sequential Access Model (ISAM) database. Though not a true relational database, the relational schema diagram below approximates the CEDMS database model.

CEDMS used three linked databases: Patient, Referring Physician and Endoscopy. The Patient Database contained a record for each patient upon whom an endoscopic procedure was performed. Each Patient Record stored a person’s name, date of birth, gender, home address, hospital ID number and a list (record IDs) of the GI endoscopy procedures performed on that patient. The Endoscopy Database contained a record for each procedure performed including: type of endoscopy (e.g. Upper GI Endoscopy, Colonoscopy), the reasons for the endoscopy, prior radiology findings and the endoscopy findings (including histology).

As a hard disk was not within the project’s budget, we had to devise a method of storing and retrieving several thousand patient and endoscopy records using multiple 140K floppy disks. To achieve this goal we: (1) implemented sparse endoscopy records (see below) that allowed CEDMS to store approximately 1,000 endoscopy records per floppy disk and (2) implemented an algorithm that would prompt the user to insert the appropriate floppy disk from a set of disks storing patient and endoscopy records.

Sparse endoscopy records were implemented using Choice Tables. These were tables of numbered choices displayed on the screen (see example below). A user entering the endoscopy data would select one or more numbered choices from a set of tables and the database would store the selection and table number rather than the full text of each selected item. This significantly reduced the size of each stored endoscopy record as only the number(s) of the items selected were stored. Using two 8 bit bytes, it would be possible to store the 16 boolean values (selected=1, unselected=0) for each Choice Table.

CEDMS supported the creation and modification of new choice tables when designing a database. Multiple tables per database were supported with up to 16 selection items per table and support for multiple selections within a table. When retrieving data the stored Choice Table boolean values were used to retrieve and display the text associated with each selected item .

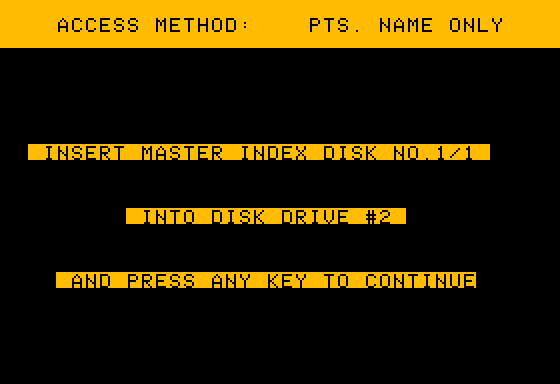

As patient and endoscopy records would be stored across multiple floppy disks an automated method for prompting the user to insert the correct floppy disk was needed. To achieve this goal we created a set of pre-formatted floppy disks to store patient records based on the first letter of the patient’s last name. Rather than creating a set of 26 patient record disks ( ‘A’ to ‘Z’) we examined the 1981 Dublin telephone directory to approximate the statistical distribution of these last name first letters in the Irish population. This allowed us to create an extensible set of 9 floppy disks that could (in total) store approximately 5000 patient records per disk set, with each disk in the set assigned to one or more letters of the alphabet.

Automated prompting of the user to enter the floppy disk containing a specific endoscopy record was achieved by creating an extensible set of endoscopy data disks, each with a unique numeric identifier. When recording an endoscopy data record the disk identifier and endoscopy record number on that disk were automatically stored in the list of endoscopies linked to each patient record. CEDMS prompted the user to insert the correct data disk into the disk drive before reading or writing data. Each disk contained a unique identifier that prevented data being written to the wrong disk.

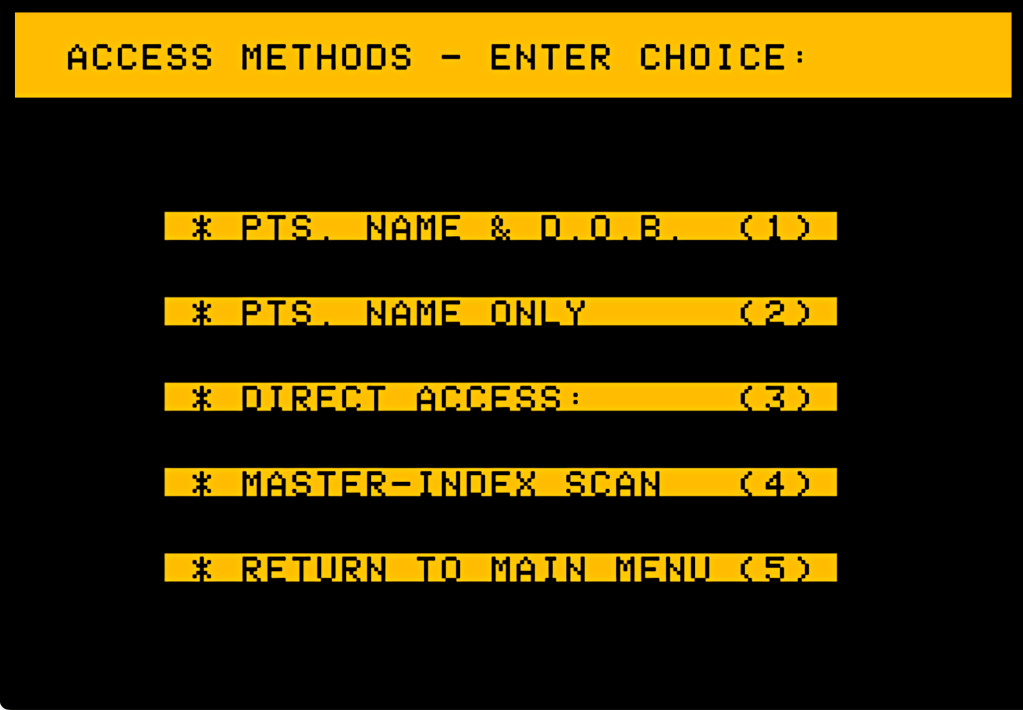

Retrieval and reporting were limited in CEDMS. The database could be queried by patient name and patient date of birth. Alternatively if a record ID was known it could be used to retrieve that record. There was also a sequential “Scan” option which allowed for partial information to be used to find one or more matching records. Once a a patient record was found the endoscopy records for that patient could be easily retrieved, viewed and printed.

In October 1981 we presented a paper on CEDMS at a scientific conference in London organized by the British Society of Gastroenterology. At this meeting presentations on related computer-based systems were also made by groups from Britain, New Zealand and the United States.

In January 1982, I started medical residency training in the United States, thus ending my role in the CEDMS project. However, work on the project continued after I left, particularly on the implementation of reporting functionality and migrating the system to a hard disk storage model.

In late 1982 CEDMS begin using a hard disk for data storage – a SyMBFile 5.25-inch Winchester Disk that came in 5MB and 10 MB configurations. The hard disk was partitioned into 12 volumes containing the CEDMS AppleSoft BASIC code and nine volumes that simulated the original set of the nine floppy-based Master Index groups that we had originally created to store patient data. The system code was modified to automatically read and write data to/from the hard disk instead of prompting the user to manually retrieve and insert the correct floppy disk. CEDMS later supported the ability to automatically format and print endoscopy reports for referring physicians.

In retrospect CEDMS was a simple standalone medical database system that reflected the limitations of the speed, memory and storage capacity of early personal computers. Other than basic patient and referring physician demographics there was no provision for the entry of textual or structured data. Searching and reporting functionality was limited and slow. However, the solution for storing several thousand endoscopy reports on a set of nine 143K floppy disks was inventive and effective, albeit with the downside of manual retrieval and insertion of disks by the operator.

CEDMS was one of the first attempts at creating a personal computer-based endoscopy data management system. Today computer systems play an important role in modern endoscopy practice by enabling efficient storage, processing, and retrieval of high-resolution images and videos captured during procedures. Modern systems facilitate integration of endoscopy data with electronic health records (EHRs), ensuring that patient data is securely stored and easily accessible for diagnostic and treatment planning. Advanced software tools analyze endoscopic images, supporting physicians with real-time insights and aiding in the early detection of abnormalities.